[Excerpt from ‘The Cheeky Monkey – Writing Narrative Comedy‘]

The saying ‘Tragedy is when it happens to me; Comedy is when it happens to you’ is right, but it only tells half the story. The second half of the line should be ‘Comedy is when it happens to you because of something you’ve done’. Sure, it’s not as catchy, but it’s an essential principle for writing narrative comedy.

The Hope Principle’s lack of a truly heroic comedy hero stems from Aristotle’s thoughts on stories. In his book, Poetics, he claimed that comedy is ‘an imitation of inferior people’. He believed that low status characters (such as slaves), particularly those with ideas above their station, are the most common characters in comedy because they’re prone to moral badness.

Higher status characters, he said, are less common due to their social strengths, but they can be funny if they have deep, intrinsic personality flaws that make them prone to weakness or sin.

Aristotle maintained that tragedy characters are typically of high birth and morals. Tragedy only needs its characters to behave badly when the plot demands it. For instance, everyone in the path of a tidal wave can be a paragon of goodness, only driven to selfish action when the wave is upon them. Sure, the story of their destruction may not be interesting, but it will certainly be tragic.

The flaws of comedy characters ensure they deserve what they get. Michael Dorsey in the comedy-romance, Tootsie, gains the world by pretending to be a woman. When he finally decides to do the right thing, he loses everything. This story aims to make us laugh.

Tragedy characters can get what they don’t deserve. Jack in James Cameron’s tragic romance epic, Titanic, is a brave and noble fellow who goes down with the ship, losing his life and love. This story aims to make us cry.

Being hit by a car is in itself a tragic event. Random and unfair, it’s not funny. So, how do we make it funny? As Aristotle implied, we musty make the car accident the victim’s own fault. Seeing someone come undone due to their own actions changes an otherwise random tragic event to a comic consequence for their sins or shortcomings.

If a character is hit by a car because they previously cut the car’s brakes (in the hope of killing the driver), they become a victim of their own crime. This irony alleviates the audience’s natural sense of affinity with the victim. Anything, including painful death, is acceptable to us.

Serves them right! The wicked Lord Farquaad (Shrek) is swallowed by a dragon and is last seen in the creature’s stomach, paddling in its digestive juices.

Children laugh at this. (One rare exception to this principle is ‘Kenny’ from South Park, an innocent kid who’s killed by random events on a weekly basis. Kenny, however, is a satirical construct built for precisely, and almost exclusively, the purpose of dying ‘tragically’. With this understanding, the audience has already put their affinity for the poor kid aside and the cruelty of the satire inspires laughter.)

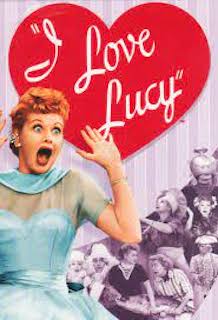

Of course, the trouble caused by a sinful action need not be as drastic as a car crash. The principle can apply to any stake-raising/resolving event. Lucy (I Love Lucy) puts on a putty nose to disguise herself from William Holden (whom she accidentally humiliated previously). But when Lucy goes to light a cigarette, her putty nose catches fire. Lucy is exposed and humiliated. An observer who knew nothing of the situation might see Lucy’s reaction to being caught out (dismay, distress and embarrassment) as tragic.

However, knowing that the event was Lucy’s fault gives us distance from, and moral license to laugh at, her pain and humiliation. It serves her right for not being honest to William Holden. Thanks to her behaviour, we feel affinity with Lucy – but not sympathy.

In some cases, a benign character’s flaws, not their sins, can lead to comic events. For instance, a generous character who donates their time to fix a car, despite the fact they have little mechanical knowledge, can inspire laughter when the car runs them over. Though the kind character is trying to be helpful, they are too stupid or innocent to know the task is beyond them.

Gilligan (Gilligan’s Island) is a well-meaning but naïve character who discovers some tree-sap that he’s confident can glue the castaways’ boat back together. Of course, having raised everyone’s hopes, Gilligan is scolded when the sap is proven useless when the boat sinks.

A high-status character’s flaws can inspire other characters to inflict punishment upon him. In the comedy film Trading Places, Dan Aykroyd plays ‘Louis Winthorpe III’, a wealthy stockbroker who’s both arrogant and spoilt. Because of these qualities, his employers select him for a nasty lesson in humility. Watching Winthorpe unravel is funny because his negative qualities make his reduction to poverty seem deserved. (Once he’s learnt humility, however, he becomes more heroic in the audience’s eyes.

He’s then able to turn the tables upon his employers. Because of their callous manipulations, they suffer terrible [and humorous] losses.)

The Own-Fault Principle keeps characters active in their own journey, as opposed to being innocent victims of something that could happen to any of us at any time.

If an event in a script lacks comic punch, it may be simply due to the fact that your character/s are victims of Fate. Try finding a cause-and-effect chain of events in which your characters inadvertently set themselves up for a fall.

[Excerpt from ‘The Cheeky Monkey – Writing Narrative Comedy‘]