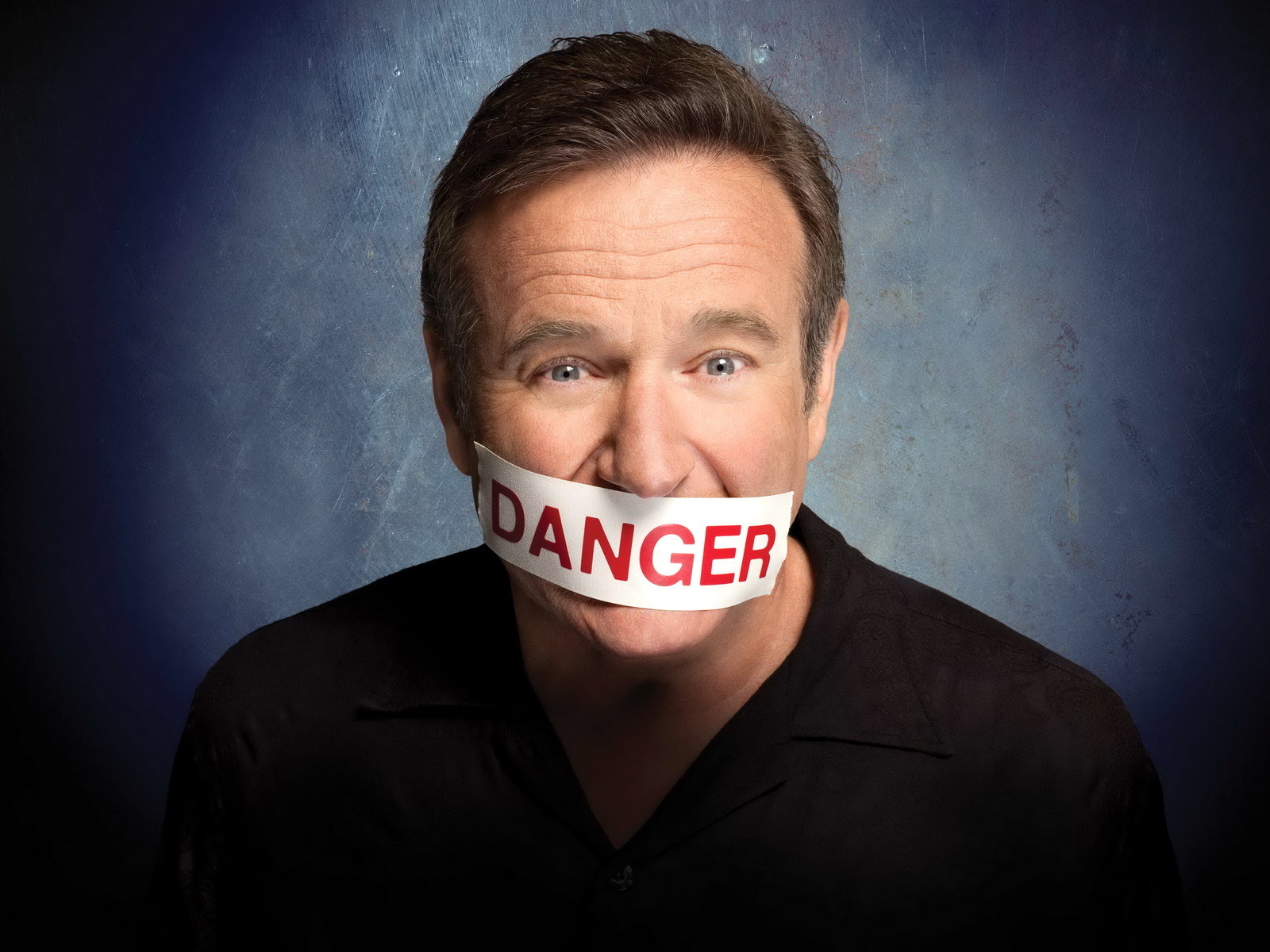

ROBIN WILLIAMS VS THE BLACK DOG (By Tim Ferguson)

The ‘black dog’ is a comedian’s best friend. Robin Williams knew well that generating humour for an audience is an effective way to combat depression for the comic and audience alike.

“Comedy is acting out optimism’, he said. Not creating it, or reinforcing it – acting it out. Optimism was Robin’s plaything, a torch he conjured to cut through the darkness.

His comic improvisations were legendary. He baffled and delighted Michael Parkinson and Ray Martin by commandeering their TV interview shows for an hour of fevered imaginings. They were road-kill in his hilarious path.

We can never know for sure the causes of his choice to die, but his long battle with depression seems a possible culprit.

Many people are fascinated by comedians’ depression. The notion of a crying clown, a dark jester with a beef, is intriguing. The contradiction lies at the heart of how comedy works and the function it serves.

To understand how Robin made millions of people laugh, perhaps start by looking at laughter itself. Why do people laugh? It’s a very odd way to behave. Cackling, rolling on the floor, struggling to breathe…

Strangely, the laughter response has all the hallmarks of the human body’s response to fear. A frightened person experiences involuntary and spontaneous expulsion of breath, adrenalin, endorphins, bladder weakness, shallow breathing, yapping, screaming, hissing… The act of laughter resembles this response to fear. It seems that somehow our brains recognise the difference between genuine danger and play, diverting the fear-response to laughter’s raucous spasms.

A comedian’s task is to create surprises that confirm truths that in another context might create distress, anxiety or a loss of status. Comedy works best when it is inappropriate, dangerous or painfully incisive. As comedian Steve Martin says, comedy is not pretty.

Depression has been described as being not so much an irrepressible sadness, but as a perpetual, abiding anger, a rat on a wheel. Anger is a common emotional response to ongoing fear or anxiety. Everyone snarls at threats. Robin Williams tried to make us laugh at them.

To survive and thrive, a comedian spends a lot of time in anger’s territory. We distil inequities, absurdities and imbalances to build diversions. Then we distract an audience for long enough for us to spring a trap of accepted truth. Such comedic contrivances exploit the things that make people confused, upset or frustrated. Many comics, either out of habit or compulsion, are practiced at manipulating these elements.

This means ongoing anger, like the depression Robin Williams spoke of fighting, can be a comic’s creative tool. Anger can also be our inspiration. It can goad us to write a show, to go on tour and preach our taunting gospels.

The downside is the black dog’s barking keeps us awake at night. Comics don’t sleep well. A comedian mate of mine calls her anger ‘a drumming bunny with a gun’. (She refuses to be named lest the audience realises she isn’t as happy-o-lucky as she appears.)

When comics wrestle with black dogs, we do so impatiently. Why write a thesis when a joke gets there faster? Robin William was a master of cutting to the chase.

He didn’t have to look far to find sources of injustice or nonsensical rationales. ‘People say satire is dead,’ he said. ‘It’s not dead; it’s alive and living in the White House.’ And though his Mork-ish comedy played at optimism, he often played dirty (‘Never pick a fight with an ugly person, they’ve got nothing to lose.’)

The great comedian’s fight with depression was never an easy one, but he fought bravely for his corner. ‘You’re only given one little spark of madness,’ he said, ‘you mustn’t lose it.’ Managing that spark may have been more of a challenge than he was able to maintain.

Williams said he believed words and ideas can change the world. His jokes could do that too. (if you laugh at something, it’s proof that no matter how unpalatable it may be, you agree with it. See his joke above about ugly people.) Robin’s comic improvisations as the reckless radio host in ‘Good Morning Vietnam’ gave audiences a new perspective on the war that had robbed America of its optimistic confidence. The Vietnam War was hell, he seemed to say, so keep asking questions of power. His jokes gave audiences emotional distance from the war, distance from which they could reassess their nation’s actions.

Robin’s encouragement to ‘Carpe Diem’ (‘seize the day’) in the movie ‘Dead Poet’s Society’ has become a touchstone for millions, a common sense approach to our short lives. It’s become a cliché that many will bandy about in his passing.

We all feel a terrible loss at Robin’s passing. He was a titan of the comedy industry, generous with his wisdom and blessed with a curious, restless genius.

Williams said, ‘In America they really do mythologise people when they die.’ In his case, they certainly will mythologise – and they should. He was proof that a clown can change the world.

(This article first appeared in The New Daily thenewdaily.com.au)