Continuing from ‘How to make Your Comedy Believable – Part 1’

Drama’s Demanding Imperative

Drama faces a demanding imperative – it must mimic reality so the audience can suspend their disbelief. A dramatic film, for example, works best for its audience when they can submerge themselves into

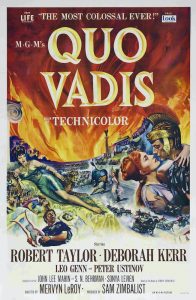

its world and experience the events and characters’ choices so they may mimetically learn from the experience. If an element of the movie feels fake – whether it’s bad acting, lighting, editing, writing – see audience recoils from the experience. When a Centurion in the 1950s Roman epic Quo Vadis was inadvertently shown wearing a wristwatch, audiences felt the immersive experience the rest of the movie invited had been ruined for them.

Comedy experiences no such finicky expectations from its audience. We can enjoy a comic depiction of a Roman epic in which every character wears a wristwatch and carries a cellphone. We are not watching to learn, we are watching to laugh.

With the imperative of faux realism removed, comedies nonetheless must service its audience’s expectation of believability. They may not think the characters and events are realistic, but they have other, equally compelling demands of a comic story.

Comedy characters are grounded in a credible response

How does narrative comedy in films, sitcom, sketch, plays or webseries get away with its flimsy regard for the ebb and flow of real life? The answer is found in the actions and reactions of the characters. Though they may be exaggerated or compressed compared to real life, they are nonetheless grounded in a credible response to the situation. In a drama, the characters’ actions might be more nuanced and inhibited, but are otherwise essentially the same.

Comedy occurs when characters attach exaggerated importance to something we can see is not that important, or alternately attach little importance to something we can see is crucial. Frasier locking his brother in a toilet might be appropriate if Niles were a communist and being sought by Nazis. The stakes would match the action and Niles would hide in the toilet without protest. Here, however, Frasier is merely trying to impress his date. In reality, this situation would never occur: he’d simply allow the girl to arrive, explain the situation and cope as best he could.

We accept the scenario however because it’s based in truth: we know Frasier is a stickler for appearances. His action is extreme but stems from a quality that Frasier is already known for. His disproportionate reaction breaks the bond of empathy and allows us to laugh at the outcome.

Similarly, we know that Niles can be over-emotional and desperately loves Daphne, so seeing him too distraught to protest at being locked in a toilet, although exaggerated, is consistent with his personality and thus we accept it.

These extreme or disproportionate reactions are what the audience has tuned in for and are what makes the situation comedic. They’ll only jack up when characters act against their nature for no apparent reason.

Comedy is Fighting Time

Like everything in a sitcom, plot development is subject to one overriding priority: time

This is often done by highlighting only the traits that will be challenged by events in the story. In Seinfeld, George Castanza has many personality shortcomings but usually only one or two of them are exploited in a given episode. For instance, in ‘The Hamptons’ (by Carol Leifer and Peter Mehlman), George’s pride and pettiness are exposed when he goes out of his way to see a woman naked because she has seen him naked and chuckled at his pool-shrunken manhood.

Narrative Comedy’s Distilled Characters

Typically, new or cameo sitcom characters enter the action at a run, already engaged in or catalysing the story with little if any time taken to establish them. This is why so many sitcom cameos are archetypes or caricatures: the writers show only that which will push the story forward.

Excerpt from The Cheeky Monkey – Writing Narrative Comedy