Absurd comedy, or humour, mocks any detailed analysis. Typically, each absurd joke or scenario is a world unto itself and has few specifics in common with other jokes in the genre. But there are some general guidelines to the art.

It’s arguable that all comedy is absurd. All humour points to the absurd in life, in that it generally turns on a logical contradiction or defies a logical expectation. But Absurd Humour seems to ignore contradiction and neutralising expectation in favour of a kind of negation – an entirely distinct concept.

Monty Python’s absurd comedy

Absurd comedy such as the work of Monty Python shows largely intelligent and rational characters reacting in realistic ways. It’s simply the situation that’s absurd. Even if the characters are operating under an absurd belief or obsession, once we accept that they genuinely believe in it, we can see that they are behaving rationally. In The Holy Grail, The Black Knight believes he can still put up a fight, though his arms and legs have been hacked off (‘I can still bleed on you!’) Once we accept that he believes it, we accept that he’s behaving rationally on his own terms. The implausibility of his inflexibility is the key to the comedy.

Absurd comedy such as the work of Monty Python shows largely intelligent and rational characters reacting in realistic ways. It’s simply the situation that’s absurd. Even if the characters are operating under an absurd belief or obsession, once we accept that they genuinely believe in it, we can see that they are behaving rationally. In The Holy Grail, The Black Knight believes he can still put up a fight, though his arms and legs have been hacked off (‘I can still bleed on you!’) Once we accept that he believes it, we accept that he’s behaving rationally on his own terms. The implausibility of his inflexibility is the key to the comedy.

Absurd or nonsense humour highlights the ridiculousness of life, pushing normally accepted realities to nonsense extremes, giving the audience a fresh perspective. (In Monty Python’s The Meaning of Life, a Catholic mother and father have followed the dictates of the Vatican by breeding dozens. They have bred so many children, when a baby plops out of the mother, she is neither surprised nor excited. The Vatican’s view that ‘every sperm is sacred’ is taken to its extreme and then given a nudge – they have so many children, the parents are forced to sell them for scientific experimentation.)

Through the juxtaposition of incongruous entities, personalities, values or behaviours, absurd humour creates scenarios in which the characters have nonsensical manifestations, aims or perspectives. (In The Holy Grail, the Knights of Ni shout the word ‘Ni!’ to dominate their foes. Before the terrified King Arthur can pass them, they demand he bring them, of all things, a shrubbery.)

The use of random elements like ‘a shrubbery’ pervades this type of humour.

Anthropomorphism

Anthropomorphism is common in absurd humour. And it’s not just animals that can have human characteristics. In the absurd world, even lunchboxes can have personalities and driver’s licenses and a human being can think they’re a lunchbox.

Absurd humour can play upon the absurdity within a joke itself, either reversing, neutralising or furthering that absurdity for a laugh.

How old is absurd humour?

Absurd humour has been around at least since the Middle Ages.

In The Nun’s Priest’s Tale’(Canterbury Tales), Geoffrey Chaucer (1343-1400) tells of a fox chasing a rooster round a barnyard, but he uses lofty, heroic language more suited to a grand epic. This absurd metaphor raises animals to the level of humans, no doubt implying that humans can be lowered to the level of animals.

Lewis Carroll’s Alice In Wonderland is similarly anthropomorphic – the animals in Wonderland talk and have largely human concerns.

‘Dada’ artists in sketch comedy

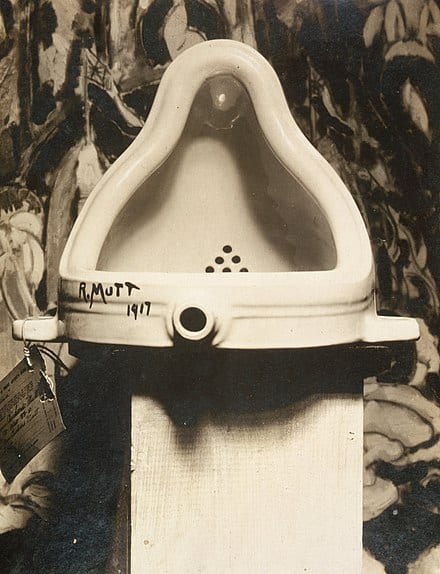

Absurdism became prominent during World War I, when ‘Dada’ artists began seriously questioning institutions, language and culture. The finest example of the period is Duchamp’s inverted urinal (Fountain by ‘R.Mutt’). The art world and society at large were rocked by the suggestion that anything could be art if the artist said it was.

The Dada influence remains in absurdist TV sketch humour today. A typical Dada method was to throw scraps of paper inscribed with words into a hat. The Dadaists would remove some of the pieces of paper and devise poems based upon the words they’d extracted from the hat. Some modern British sketch shows (i.e., Little Britain and Big Train) often seem to rely on a similar apparent randomness. (One example has Ming The Merciless vacuuming his suburban home. Another features a dozen jockeys trying to put out a house-fire.)

Randomness as absurd comedy

Randomness is a component of much absurd humour:

Q: How many absurdists does it take to change a lightbulb?

A: An orange.

– Unattrib.

This Obvious ‘Using a statement against itself’ joke defies our expectation of a more-considered punchline. Once the key element ‘Absurdists’ is mentioned, the ingredient of the punchline is almost irrelevant. It could be ‘An Elephant’ or indeed ‘A Urinal’. The choice of a seemingly random punchline or element is typical in absurd comedy.

Haikus are easy… But sometimes they don’t make sense

Refrigerator

– Unattrib.

All the final line of the Haiku needed was five syllables.

For ten years, Caesar ruled with an iron hand. Then with a wooden foot, and finally with a piece of string.

– Spike Milligan

Having posed a ‘reality’, some absurd jokes take it one step further:

A dog goes into a hardware store and says: “I’d like a job please”.

The hardware store owner says: “We don’t hire dogs, why don’t you go join the circus?”

The dog replies: “What would the circus want with a plumber”. (Steven Alan Green)

Other Absurd gags extrapolate from their premise to an absurd conclusion:

My friend George is a radio announcer. When he walks under a bridge, you can’t hear him talk.

– Steve Wright

Absurd comedy and joke punchlines

Absurd jokes can rely on a punchline that plays with the absurdity itself:

Shifting perspective from the absurd to the realistic is a good way to throw an audience off-balance. The following Obvious/Absurd two-part joke is an example:

Q: How do you fit two elephants into a Mini Minor?

A: One in the front and one in the back.

Q: How do you fit four elephants into a Mini Minor?

A: Look, you’ve already got two elephants in there. There’s no way a Mini is going to seat another two.

Anon

Every day absurd comedy

Absurdity can highlight everyday human concerns:

The Monty Python ‘Argument Sketch’ features a Customer who has paid a professional Arguer to have an argument. Once this absurd scenario is accepted, the sketch bounces between the Customer, who feels he’s being ripped off, and the Arguer who rejects everything the customer says.

MAN: …This isn’t an argument.

MR VIBRATING: Yes, it is.

MAN: No, it isn’t. It’s just contradiction.

MR VIBRATING: No, it isn’t.

(The Customer’s frustration at the intransigent Arguer reflects that of all customers who haven’t gotten what they paid for.)

Any of the other gag principles can be used for Absurd comedy.

Excerpt from ‘The Cheeky Monkey – Writing Narrative Comedy’ [Currency Press]