What do the following pieces of comic dialogue have in common?

1.

ALLAN: What are you doing Saturday night?

MUSEUM GIRL: Committing suicide.

ALLAN: What about Friday night?

(‘Play It Again, Sam‘)

2.

KIM: I’m not a size 16, Mum. I’m a size 10.

KATH: Country Road’s size 10. (‘Kath & Kim‘)

3.

LUCILLE: Get me a vodka rocks.

MICHAEL: Mom, it’s breakfast.

LUCILLE: And a piece of toast.

(‘Arrested Development‘)

Identifying the principle underpinning these exchanges requires some thought. Devising the exchanges takes even more thought. Strangely, there is an assumption that because a comic scenario or joke is simple, inventing it must require less thought from both writer and audience than, say, a dramatic emotional exchange.

Without knowing the principle underpinning these exchanges, writing something similar can pose as much of a challenge as finding the shortest route to Rome. (Yes, all roads lead to Rome but without a map, the simplest route takes time and practice to find. And it won’t help you from a new location.)

To test your natural comedy skills, write an original exchange using any topic, characters and setting that resembles the exchanges above.

Okay, now you’ve skipped over the baffling task above, read on.

Most people don’t know the technical principle that connects these exchanges. This lack of knowledge is not a sign of stupidity, or a lack of skill and talent. For the average audience member, this lack of knowledge is unfortunate but allowable. For screenwriters, authors or playwrights, not knowing the principle connecting the jokes is unforgivable – and may explain why they are forced to work a second job to pay their bills.

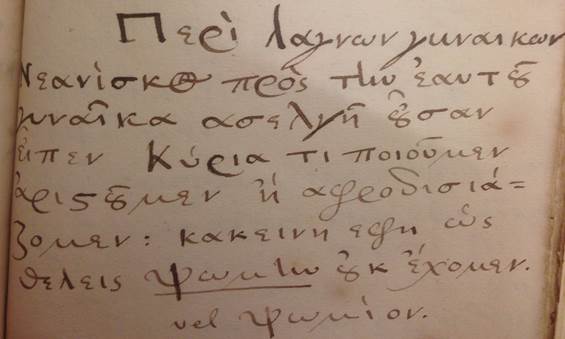

The principle is simple and forehead-slappingly obvious when you know it. The comic principle is ancient. One of the world’s the oldest recorded jokes (by Philogelos, circa 400AD) goes like this:

“A Soothsayer reads an Abderite’s fortune and says, ‘I see you will have no children.’

The Abderite scoffs. ‘Fool,’ he says. ‘I have six children.’

The Soothsayer replies, ‘Hm… Tell them to be careful.’”

So what’s the link between the jokes? It’s not their subject matter. Each of the three exchanges involves different topics – dating, jobs and drinking.

It’s not rhythm. Two of them (1 and 3) follow a classic tripartite pattern, but the second is a two-line pattern.

It isn’t the characters. Each plays on the unique qualities and immediate desires of very different personalities.

Two of the quotes are American and one is from one of Australia’s most popular sitcoms, so nationality has nothing to do with the connection.

And the Philogelos joke is from Ancient Greece, so has no direct contemporary, cultural or regional link to the three segments of dialogue.

The connection is a simple narrative comedy principle. A ‘principle’ is not a formula and it certainly isn’t a rule. It acts as a framework, much in the way scaffolding can be used to construct a building. The buildings may be made of differing materials – bricks, wood, mud – but the scaffolding used to guide the construction is the same. Or, to put it another way, a hair-roller provides a fixed function. Hair colour, strength or style has nothing to do with the function of a hair-roller itself. The roller’s function concerns only shaping the hair its wound in.

This particular comic principle can be found in narrative comedies of all kinds. Be warned: once you know the principle, you won’t forget it. You will recognise it in virtually every comedy you see.

The principle is what comedy writers and producers call a ‘gag’. They’ve bought their beach houses through regular application of gags, gags and more gags. When comic characters, situations, themes and story/scene structure are developed, the next layer is the generous distribution of gags. (A typical sitcom script contains four gags per industry-format page.)

A comedy without gags has little chance of fulfilling the core imperative of any comedy – audience laughter.

Spontaneous and involuntary laughter is compulsory in comedy. Wry smiles, knowing winks and mutters of ‘Well played, sir/madam, well played,’ are all very well, but laughing out loud is an audience demand. Only an ignorant snob (or a lazy writer) would define the primary purpose of comedy any other way.

To create out-loud laughter, writers must create a surprise which accords with the audience’s perception of truth. This is why one man’s comedy is another’s flatline. Subject matter, and the (often subjective) truth being highlighted with it, must be known, palatable or of interest to the audience.

Without affinity of any kind, a joke dies. Greenies, whale-hunters and Young Liberals each have their no-go zones. Political humour works best if the audience is onside. If they don’t agree with the subjective truth of a joke, audiences can quickly become bored or angry.

People who claim to have open minds soon reveal they are not open to everything. Swingers and Methodists might enjoy the same jokes, so long as the subject matter truth being imparted are broadly acceptable to them. But everyone has a soft spot, so to speak.

The passage of time doesn’t always cause a joke to lose its sting. The Philogelos joke above may seem harmless (it’s 1600 years old) unless you’ve lost a child.

The principles of comedy, however, can be applied to any subject matter, be it topical, smutty, intellectual or childish. Once the gag is constructed, the principle is only apparent to someone who knows what to look for. Like hair-rollers, no part of the principle is left behind.

The three narrative jokes and the Philogelos gag above comply with a principle known as the ‘Inescapable Conclusion’. In the case of Woody Allen’s ‘Play It Again, Sam’, ‘Allan’ is aiming to get a date. The Museum Girl’s plans for suicide don’t deter him. The date is, for now, inescapable.

Gina Riley’s ‘Kim’ may wish to be seen as a Size 10, but only if that size is in the more generous Country Road sizing.

And Lucille (created by Mitch Hurwitz) is getting her vodka no matter what.

And Philogelos’ Abderite may scoff at the Soothsayer’s dire prediction, but the future of his children is not in the stars. The premise of each exchange is fought against but cannot be denied.

This particular comic principle relies on the audience falling for a simple trick of misdirection. In each example, they are lead to assume there will be a twist on the premise – perhaps Woody will give up, Kath will admit she is a Size 16-and-a-half, Lucille will delay her morning vodka and for a moment, we thought there was something to rejoice.

When each premise is proven to be inescapable, the truth of the characters acting true to form, and the inevitability of the situation comes as a minor surprise, a surprise that figures. Most punchlines cause an audience member to think ‘I should’ve seen that coming!’ If the audience does see the punchline coming, they will duck the punch. And they probably won’t laugh.

The ‘Inescapable Conclusion’ gag type is to be found in many narrative comedies or one-liners. The American comedian Martha Raye opined ‘Ask any girl what she’d rather be than beautiful and she’ll say “More beautiful”.’

The principle is ancient, presumably dating back to the Stone Age.

How does the principle create laughter if none of the scenarios seems like a delightful experience? The notion of being trapped without any chance of escape doesn’t seem immediately or universally funny (ask any inmate). Here’s how it works:

A comic scenario is translated by our higher perceptions to our primal responses (some of which are located around the amygdala at the base of the brain). Then a response of involuntary noise, adrenalin, endorphins, shallow breathing, bladder- and bowel-evacuation is initiated by the lower brain.

The higher brain (which knows the ‘Inescapable Conclusion’ scenario is merely play) diverts these responses from fear/flight reactions to danger into laughter. So a comedy audience member might say ‘It was so funny, I laughed, got a boost, felt giddy, couldn’t breathe, wet myself and cacked!’

The responses above are all fear/flight responses diverted to laughter. The connection between anxiety, fear, surprise and laughter is undeniable.

The oldest recorded joke is an Ancient Greek gag:

“An absent-minded Professor is on a sea voyage when a storm blows up. The ship begins to sink and his Slaves weep in fear.

The Professor says, ‘Don’t Weep. Rejoice! I have freed you all in my will’.

Now can you see the pattern? Knowing the principle doesn’t necessarily ruin the enjoyment of such jokes, but if you claim to be a writer of any kind, you should be aware of it. As is clear, the simplicity of the principle doesn’t restrict its broad application over centuries and across seas.

Knowing the principle allows a writer to construct a scenario and to know when the comic principle is fulfilled. The steps are either a tripartite pattern:

1. Outline the premise: “Dr. Kelso: Do you think I got to be chief of medicine by being late?

2. Challenge the premise: “Dr. Cox: No. You got there by back-stabbing and ass-kissing.”

3. Confirm the premise: “Dr. Kelso: Maybe so, but I started those things promptly at eight.” (Scrubs)

Or a two-step pattern:

1. “BERNARD: (About the job) The pay’s not great…

2. …but the work is hard.” (Black Books)

The number of comedy principles is finite. They provide frameworks for creating gags that can appeal to all kinds of people. Writers must learn these principles by trial-and-error or direct teaching.

Gag types like Character Confirmations, Self-Referentials, Distortions, Reversals, Absurdity, Extrapolations Reversals, Negations or Puns can be identified, practiced and mastered. All the narrative comedy principles have been defined. It is lazy and limiting to avoid them.

Learn comedy – write better – get work.

The conclusion is inescapable.

For more comedy writing principles attend one of Tim Ferguson’s masterclasses or read his comedy writing manual The Cheeky Monkey – Writing Narrative Comedy